The Federal Reserve is widely seen as unlikely to ride to the rescue as the stock market stumbles to begin 2022.

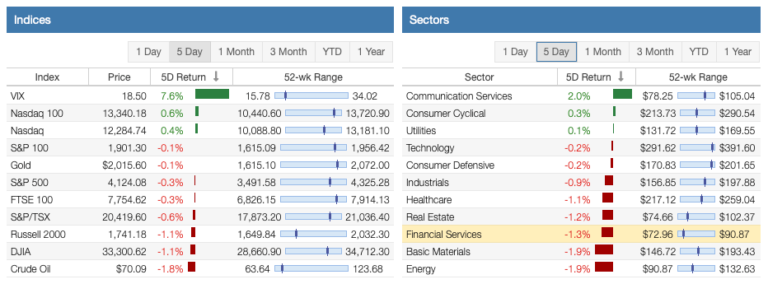

Indeed, some market watchers blamed Monday’s initial broad stock-market downturn which saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

plunge more than 1,000 points and the S&P 500

SPX,

slide 4% at its session low partly due to expectations the Fed won’t snap back into hand-holding mode when policy makers meet this week, though equities subsequently roared back to end the day higher in a breakneck intraday reversal.

Stocks are still down sharply to kick off the year, however, with the Nasdaq Composite down more than 14% from its November high to trade in correction territory, while the S&P 500 has shed 7.5% in the month to date and the Dow has lost 5.4%.

Many analysts and investors have written off, at least temporarily, what’s known as the “Fed put,” arguing that surging inflation means policy makers will be unable to deviate from plans to deliver a series of rate increases and otherwise tighten monetary policy in the months ahead.

Barron’s: Is the ‘Fed Put’ Kaput? Gone for Now but Not for Good.

The central bank’s policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee expected this week to lay the groundwork for a rate increase at its March meeting and to further discuss how fast it will shrink its balance sheet once it is ready to do so.

Also: Here’s where Fed voters stand on raising interest rates and reducing $8.8 trillion asset stockpile

Investors have talked of a figurative Fed put since at least the October 1987 stock-market crash prompted the Alan Greenspan-led central bank to lower interest rates. An actual put option is a financial derivative that gives the holder the right but not the obligation to sell the underlying asset at a set level, known as the strike price, serving as an insurance policy against a market decline.

Need to Know: Here’s what may save the stock market as Powell removes the Fed put, according to a strategist

“Last week’s price action reflected the fact that the market is in the midst of a ‘Tightening Tantrum,’” wrote Tom Essaye, founder of Sevens Report Research, in a Monday note. “And just like the ‘Taper Tantrum’ from 2013, this Tightening Tantrum won’t end until the Fed, as it did back then, reassures the market that it won’t tighten too quickly,” he said, referring to a bout of market volatility that followed a spring 2013 signal that the central bank was preparing to wind down the asset-buying program put in place during the financial crisis.

The difference, however, is that unlike 2013, the economy faces an inflation problem, Essaye said, with the Fed under enormous political pressure to get surging prices under control.

See: How Jerome Powell may try to calm the market’s frazzled nerves

“Practically speaking, that means the Fed will allow stocks to decline more before providing rhetorical comfort then they did in 2013. Put another way, as we and others have said, the ‘strike price’ on the Fed put is lower than it used to be, and it’s

lower than where the S&P 500 is trading right now,” he wrote, ahead of Monday’s market open.

More recently, stocks tanked in December 2018 as the Federal Reserve pressed ahead with a tightening cycle. The Fed in January 2019 signaled an abrupt change in course that led to rate cuts later in the year. Equities regained their footing to continue a record bull-market march that ended only with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic more than a year later.

But this time around, not only is inflation running at a roughly 40-year high, unemployment sits at 3.9% and the economy appears relatively resilient thanks to solid consumer balance sheets, analysts said.

“Put another way: until we get a further selloff in risk assets, the Fed will simply not be convinced that raising interest rates and reducing the size of its balance sheet in 2022 will more likely cause a recession rather than a soft landing,” said Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research, in a Monday note.

Still, the outcome of the Fed meeting on Wednesday could still serve to stabilize markets, said Neil Dutta, head of U.S. economic research at Renaissance Macro Research, in a note, arguing that investors may have gotten too aggressive in penciling in the pace of rate increases.

Fed-funds futures show traders see a roughly 5% chance of a 50 basis point, or 0.5 percentage point, hike, rather than a 25 basis point move, by the Fed at the March meeting, according to the CME FedWatch tool. Eurodollar futures, meanwhile, reflected a roughly 50-50 chance of a half-point move, Dutta noted, adding that history shows the Fed is much more likely to end a rate cycle with 50 basis point hike than it is to to kick off with an outsize move.

Given the current pricing in markets, “an indication that the Fed will not be starting with a 50 basis point rate hike might be enough to provide a floor under risk sentiment,” Dutta wrote.

It’s a topic that will require Fed Chairman Jerome Powell “to thread a needle” in his Wednesday news conference, wrote economists at RBC Capital Markets, in a note last week. Powell will need to continue expressing urgency about making monetary policy less accommodative while not coming across as nervous or behind the curve.

The latter would “only add some fuel to the conversation gathering momentum here now about the prospects for a 50 [basis point] hike,” they said. “We think they want to avoid going that route. We have no doubt he will be asked this during Q&A so we hope he has a good answer prepared.”

Published at Mon, 24 Jan 2022 17:10:00 -0800