Buffett’s Investment in See’s Candy

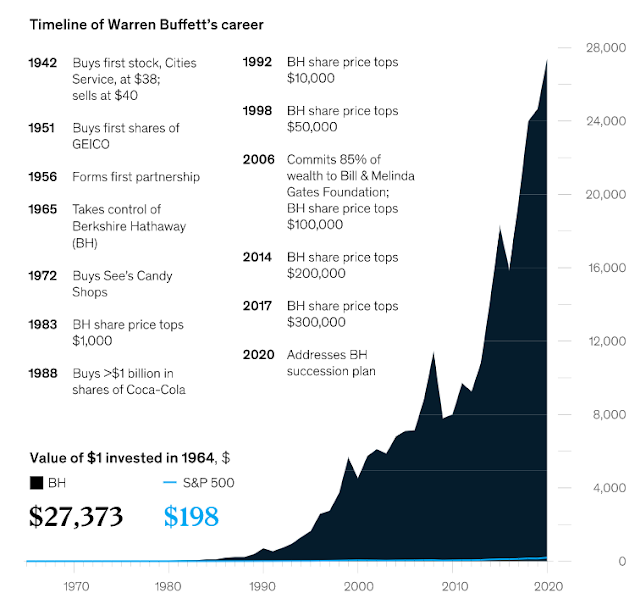

Warren Buffett is arguably the best investor of our time. He turned a struggling company called Berkshire Hathaway and transformed it into a formidable conglomerate with interests in insurance, transportation, utilities, industrials to name a few. Berkshire also spots an impressive equity portfolio worth over a quarter of a trillion dollars.

One dollar invested in Berkshire Hathaway in 1964 turned into over $28,000 by 2020.

Buffett himself is someone who has worked very hard for decades, spending 70 hours/week studying business, strategy, investing and learning from his mistakes. He has been able to successfully adapt to a variety of conditions, and apply his knowledge in a way that continues to compound his capital. He is a learning machine.

For example, Buffett started investing in companies that were selling at a portion of their asset values and in merger arbitrage situations. That was during the 1950s and 1960s, the days of his Buffett Partnership. These were the cigar butt type companies, where he would buy low and sell high, rinse and repeat. It was difficult to find cheap companies by the late 1960s however, and his asset size was very large, which meant that he had to learn a new method to compound his net worth.

He was able to pivot into investing in quality companies, which seemed optically expensive, but were really compounding machines. Buffett learned the value of investing in quality companies perhaps by accident, perhaps due to his observations or perhaps due to the influence of his long-term business partner Charlie Munger. We would never know, but the focus on purchasing quality businesses transformed him as an investor and put him on the map.

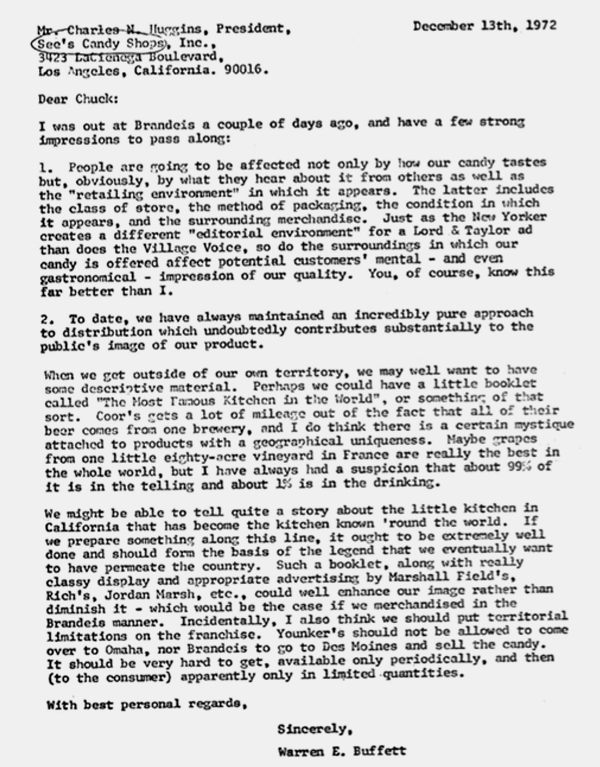

Perhaps the best example of a quality business that he bought was See’s Candy in 1972. He calls See’s Candy his “Dream Business”

The business had a strong brand recognition in the West Coast, particularly California.

There was a stable annual demand for its product, which grew slowly, but sales were consistent.

There was some untapped pricing power, which allowed Buffett to raise prices without affecting sales of the product.

The business was available at an attractive price, albeit it didn’t’ seem that way to Buffett at the time.

In fact, he almost didn’t buy this company. But luckily for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders he did.

The lesson from See’s Candies on brand recognition, pricing power, strong franchises, customer loyalty, have translated into knowledge that inspired Buffett’s investments in Coca-Cola and Apple.

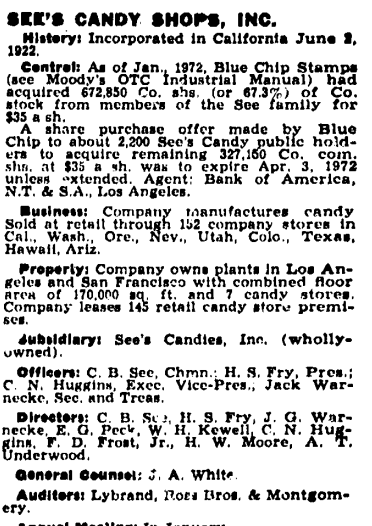

Berkshire Hathaway was able to acquire See’s Candy for $35 million. The business had $31 million in sales in 1972 and made $2.083 million in profits after taxes. The business needed a working capital of $8 million to operate.

As Buffett researched See’s, he realized that the value of the company’s intangibles, things like its brand and customer loyalty, far exceeded the numbers on paper.

If you had “taken a box on Valentine’s Day to some girl and she had kissed him … See’s Candies means getting kissed,” he told business-school students at the University of Florida in 1998. “If we can get that in the minds of people, we can raise prices.”

“If you give a box of See’s chocolates to your girlfriend on a first date and she kisses you … we own you,” the investor said in “Becoming Warren Buffett,” an HBO documentary.

“We could raise the price of the boxes tomorrow and you’ll buy the same box,” he added. “You aren’t going to fool around with success.”

See’s sold candies, and was mostly located on the west coast. It was a seasonal business which did most of its sales in the weeks between Thanksgiving and Valentine’s Day.

The business did not grow, and is still mostly located in the West Coast in California. That didn’t stop it from generating more earnings and cash flows for Berkshire Hathaway however.

By 2019 See’s had generated over $2 billion in pretax income, which was used to buy other businesses. Based on numbers I have seen, See’s Candy generated an annual income of $82 million in 2007, which was three times the amount that Berkshire paid for the company 35 years earlier.

Buffett installed managements ,and instructed them not to sacrifice quality:

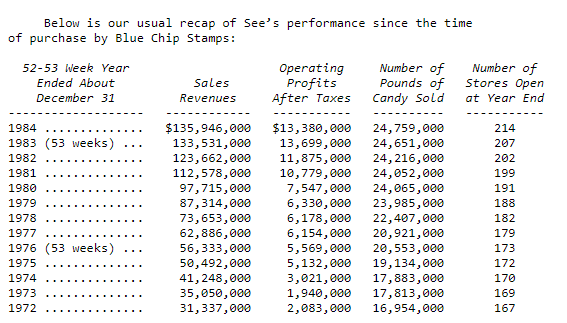

The business was able to grow very slowly. The number of shops selling See’s Candy grew from 167 in 1972 to 214 in 1984. The number of pounds of product sold grew slowly too, from 17 million in 1972 to almost 25 million in 1984.

Sales rose fivefold from $31 million in 1972 to $136 million in 1984. After tax profits rose from $2.083 million in 1972 to $13.38 million by 1984.

This was possible because of untapped pricing potential, focus on cost control while maintain quality and careful expansion.

“Long-term competitive advantage in a stable industry is what we seek in a business,” Buffett later wrote. “If that comes with rapid organic growth, great. But even without organic growth, such a business is rewarding. We will simply take the lush earnings of the business and use them to buy similar businesses elsewhere.”

Buffett’s 2007 Letter to shareholders summarizes his investment in See’s Candy and the lessons for learned:

“Charlie and I look for companies that have:

a) A business we understand;

b) Favorable long-term economics;

c) Able and trustworthy management; and

d) A sensible price tag.

We like to buy the whole business or, if management is our partner, at least 80%.

A truly great business must have an enduring “moat” that protects excellent returns on invested capital. The dynamics of capitalism guarantee that competitors will repeatedly assault any business “castle” that is earning high returns. Therefore a formidable barrier such as a company’s being the lowcost producer (GEICO, Costco) or possessing a powerful world-wide brand (Coca-Cola, Gillette, American Express) is essential for sustained success.

Our criterion of “enduring” causes us to rule out companies in industries prone to rapid and continuous change. Though capitalism’s “creative destruction” is highly beneficial for society, it precludes investment certainty. A moat that must be continuously rebuilt will eventually be no moat at all. Additionally, this criterion eliminates the business whose success depends on having a great manager.

Long-term competitive advantage in a stable industry is what we seek in a business. If that comes with rapid organic growth, great. But even without organic growth, such a business is rewarding. We will simply take the lush earnings of the business and use them to buy similar businesses elsewhere. There’s no rule that you have to invest money where you’ve earned it. Indeed, it’s often a mistake to do so: Truly great businesses, earning huge returns on tangible assets, can’t for any extended period reinvest a large portion of their earnings internally at high rates of return.

Let’s look at the prototype of a dream business, our own See’s Candy. The boxed-chocolates industry in which it operates is unexciting: Per-capita consumption in the U.S. is extremely low and doesn’t grow. Many once-important brands have disappeared, and only three companies have earned more than token profits over the last forty years. Indeed, I believe that See’s, though it obtains the bulk of its revenues from only a few states, accounts for nearly half of the entire industry’s earnings.

At See’s, annual sales were 16 million pounds of candy when Blue Chip Stamps purchased the company in 1972. (Charlie and I controlled Blue Chip at the time and later merged it into Berkshire.) Last year See’s sold 31 million pounds, a growth rate of only 2% annually. Yet its durable competitive advantage, built by the See’s family over a 50-year period, and strengthened subsequently by Chuck Huggins and Brad Kinstler, has produced extraordinary results for Berkshire.

We bought See’s for $25 million when its sales were $30 million and pre-tax earnings were less than $5 million. The capital then required to conduct the business was $8 million. (Modest seasonal debt was also needed for a few months each year.) Consequently, the company was earning 60% pre-tax on invested capital. Two factors helped to minimize the funds required for operations. First, the product was sold for cash, and that eliminated accounts receivable. Second, the production and distribution cycle was short, which minimized inventories.

Last year See’s sales were $383 million, and pre-tax profits were $82 million. The capital now required to run the business is $40 million. This means we have had to reinvest only $32 million since 1972 to handle the modest physical growth – and somewhat immodest financial growth – of the business.

In the meantime pre-tax earnings have totaled $1.35 billion. All of that, except for the $32 million, has been sent to Berkshire (or, in the early years, to Blue Chip). After paying corporate taxes on the profits, we have used the rest to buy other attractive businesses. Just as Adam and Eve kick-started an activity that led to six billion humans, See’s has given birth to multiple new streams of cash for us. (The biblical command to “be fruitful and multiply” is one we take seriously at Berkshire.)

A company that needs large increases in capital to engender its growth may well prove to be a satisfactory investment. There is, to follow through on our example, nothing shabby about earning $82 million pre-tax on $400 million of net tangible assets. But that equation for the owner is vastly different from the See’s situation. It’s far better to have an ever-increasing stream of earnings with virtually no major capital requirements. Ask Microsoft or Google.”

The lesson is to invest in quality companies, with durable competitive advantages. Even if you are a niche product, having a strong competitive position and customer loyalty is a very good position to be in. If you have the ability to raise prices, that is great for returns. Even if growth is slow, that is not a problem, especially if you require little in assets to operate, relative to the amount of free cash flows you will generate over a period of 10 or 20 years. Businesses with strong moats will be able to generate high returns on incremental capital employed, but sadly it is difficult for them to redeploy all capital back at high rates of returns. Therefore, these businesses generate more in free cash flows than they know what to do with – hence they send it back to shareholders in the form of dividends.

Published at Mon, 27 Mar 2023 04:34:00 -0700