Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell sent a clear signal interest rates will move higher and stay there longer than previously anticipated. Investors wonder if that means new lows for the beaten-down stock market lie ahead.

“If we don’t see inflation start to come down as the fed-funds rate goes up, then we’re not getting to the point where the market can see the light at the end of the tunnel and start to make a turn,” said Victoria Fernandez, chief market strategist at Crossmark Global Investments. “You don’t normally hit bottom in a bear market until the fed-funds rate is higher than the inflation rate.”

U.S. stocks initially rallied after the Federal Reserve Wednesday approved a fourth consecutive 75 basis point hike, taking the fed-funds rate to a range between 3.75% and 4%, with a statement that investors interpreted as a signal that the central bank would deliver smaller rate increases in the future. However, a more-hawkish-than-expected Powell poured cold water over the half-hour market party, sending stocks sharply lower and Treasury yields and fed funds futures higher.

See: What’s next for markets after Fed’s 4th straight jumbo rate hike

In a news conference, Powell emphasized that it was “very premature” to think about a pause in raising interest rates and said that the ultimate level of the federal-funds rate would likely be higher than policy makers had expected in September.

The market is now pricing in an over 66% chance of just a half percentage point rate increase at the Fed’s December 14 meeting, according to the CME FedWatch Tool. That would leave the fed-funds rate in a range of 4.25% to 4.5%.

But the bigger question is how high will rates ultimately go. In the September forecast, Fed officials had a median of 4.6%, which would indicate a range of 4.5% to 4.75%, but economists are now penciling in a terminal rate of 5% by mid-2023.

Read: 5 things we learned from Jerome Powell’s ‘whipsaw’ press conference

For the first time ever, the Fed also acknowledged that the cumulative tightening of monetary policy might eventually hurt the economy with a “lag.”

It usually takes six to 18 months for the rate hikes to get through, strategists said. The central bank announced its first quarter-basis-point hike in March, which means the economy should be starting to feel some of the full effects of that by the end of this year, and will not feel the maximum effect of this week’s fourth 75 basis points hike until August of 2023.

“The Fed would have liked to see a greater impact from the tightening through Q3 this year on the financial conditions and on the real economy, but I don’t think they’re seeing quite enough of an impact,” said Sonia Meskin, head of U.S. macro at BNY Mellon Investment Management. “But they also don’t want to inadvertently kill the economy…which is why I think they’re slowing the pace.”

Mark Hulbert: Here’s strong new evidence that a U.S. stock-market rally is coming soon

Mace McCain, chief investment officer at Frost Investment Advisors, said the primary goal is waiting until the maximum effects of rate hikes are translated into the labor market, as higher interest rates bring home prices higher, followed by more inventories and less constructions, fueling a less resilient labor market.

However, government data shows on Friday the U.S. economy gained a surprisingly strong 261,000 new jobs in October, surpassing a Dow Jones estimate of 205,000 additions. Perhaps more encouraging for the Fed, the unemployment rate rose to 3.7% from 3.5%.

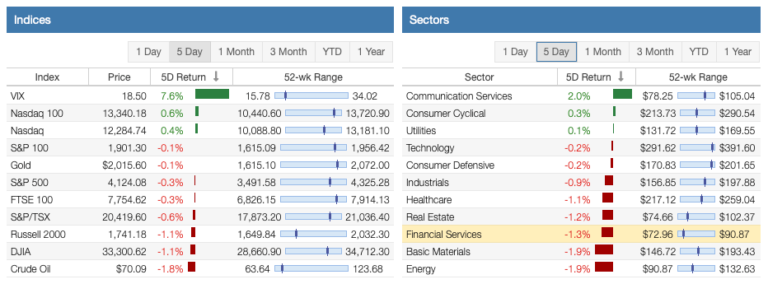

U.S. stocks finished sharply higher in a volatile trading session Friday as investors assessed what a mixed employment report meant for the future Fed rate hikes. But major indexes posted weekly declines, with the S&P 500

SPX,

down 3.4%, the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

falling 1.4% and the Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

suffering a 5.7% decline.

Some analysts and Fed watchers have argued that policy makers would prefer equities remain weak as part of their effort to further tighten financial conditions. Investors may wonder much wealth destruction the Fed would tolerate to destroy demand and squelch inflation.

“It’s still open for debate because with the cushion of the stimulus components and the cushion of higher wages that a lot of people have been able to garner over the last couple of years, demand destruction is not going to happen as easily as it would have in the past,” Fernandez told MarketWatch on Thursday. “Obviously, they (Fed) don’t want to see equity markets totally collapse, but as in the press conference [Wednesday], that’s not what they’re watching. I think they’re okay with a little wealth destruction.”

Meskin of BNY Mellon Investment Management worried that there is only a small chance that the economy could achieve a successful “soft landing” — a term used by economists to denote an economic slowdown that avoids tipping into recession.

“The closer they (Fed) get to their own estimated neutral rates, the more they try to calibrate subsequent increases to assess the impact of each increase as we move into a restricted territory,” Meskin said via phone. The neutral rate is the level at which the fed-funds rate neither boosts nor slows economic activity.

“This is why they are saying they’re going to, sooner rather than later, start raising rates by smaller amounts. But they also don’t want the market to react in a way that would looseen the financial conditions because any loosening of financial conditions would be inflationary.”

Powell said Wednesday that there remains a chance that the economy can escape a recession, but that window for a soft landing has narrowed this year as price pressures have been slow to ease.

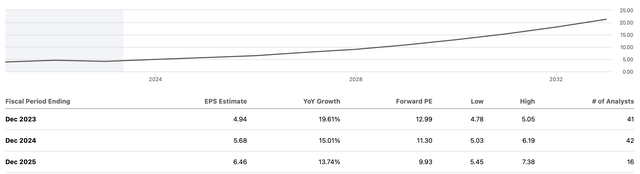

However, Wall Street investors and strategists are divided on whether the stock market has fully priced in a recession, especially given relatively strong third-quarter results from more than 85% of S&P 500 companies that reported as well as forward looking earnings expectations.

“I still think that if we look at earnings expectations and market pricing, we don’t really price in a significant recession just yet,” said Meskin. “Investors are still assigning a reasonably high probability to soft landing,” but the risk resulting from “very high inflation and the terminal rate by the Fed’s own estimates moving higher is that ultimately we will need to have much higher unemployment and therefore much lower valuations.””

Sheraz Mian, director of research at Zacks Investment Research, said margins are holding up better than most investors would have expected. For the 429 index S&P 500 members that have reported results already, total earnings are up 2.2% from the same period last year, with 70.9% beating EPS estimates and 67.8% beating revenue estimates, Mian wrote in an article on Friday.

And then there are the midterm congressional elections on Nov. 8.

Investors are debating whether stocks can gain ground following a close-fought battle for control of Congress since historical precedent points to a tendency for stocks to rise after voters go to the polls.

Anthony Saglimbene, chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial, said markets typically see stock volatility rises 20 to 25 days prior to the election, then dip lower in the 10 to 15 days after the results are in.

“We’ve actually seen that this year. When you look from mid and late-August into where we are right now, volatility has risen and it’s kind of starting to head lower,” Saglimbene said on Thursday.

“I think one of the things that’s kind of allowed the markets to push the midterm elections back is that the odds of a divided government are increasing. In terms of a market reaction, we really think that the market may react more aggressively to anything that’s outside of a divided government,” he said.

Published at Sat, 05 Nov 2022 08:38:00 -0700